main content Shaking Up Disaster Preparedness With Video Games

Using video games as research and outreach tools, an L&C team takes an interdisciplinary approach to disaster preparedness.

Story by Hanna Merzbach BA ’20

Photos by Nina Johnson

California has the San Andreas. Several states in the Southeast have the New Madrid. And here in the Pacific Northwest, we have the Cascadia. These major faults—and hundreds of smaller and more moderate ones—crisscross the United States, underscoring the planet’s constant seismic activity.

In the Pacific Northwest, a 600-mile fault line, called the Cascadia Subduction Zone, stretches off the Pacific Coast. The last major earthquake along the Cascadia, estimated to be about a magnitude 9, occurred in 1700. Researchers believe the next earthquake could happen at any time.

Liz Safran, associate professor of geological science, is director of the Environmental Studies Program and the Earth system science minor. What’s unusual about our current situation, Safran says, is that we realize a disaster is coming: “We’re in that ‘before’ moment when we know things can be done.”

But, she says, the Pacific Northwest is dangerously unprepared due to a lack of “earthquake culture”—no living person witnessed the last big quake in the region. Many have experienced only smaller shakes.

About a decade ago, recognizing the region’s vulnerabilities, Safran turned her attention to preparing residents for the future “big one.”

“I started thinking there’s really nothing more important for me to work on than trying to get people ready for this,” Safran says.

I started thinking there’s really nothing more important for me to work on than trying to get people ready for this.”

Liz Safran, Associate Professor of Geological Science

An Interdisciplinary Approach

Safran’s brainchild has turned into a multiyear research project at Lewis & Clark. The project focuses on what motivates people to prepare for natural disasters—specifically young people, ages 18 to 29.

Preparedness messaging often targets families and homeowners, leaving young people vulnerable. But young adults—given their physical capacity, creativity, and ability to mobilize—have a vital role to play in the region’s disaster response.

What’s the best way to reach young adults? One answer, Safran says, may be video games. Instead of offering prescriptive information, games allow players to learn through doing. “Video games seem like a good medium because they’re all about problem-solving,” says Safran.

To design and study a video game simulating a real-life quake situation, Safran realized she needed help. “It’s really not a geologic problem, this lack of preparedness,” she says. “It’s a human problem.”

In 2016, Safran assembled an interdisciplinary faculty team to pursue the project. The team is still in place today. Erik Nilsen, associate professor of psychology, specializes in human-computer interaction and leads the design and execution of the team’s experiments. Peter Drake, associate professor of computer science (and an avid gamer), oversees programming and game development. Bryan Sebok, associate professor of rhetoric and media studies, plays a crucial role in constructing the game’s narrative and facilitating focus groups. Safran manages the project and is the liaison with local emergency managers to ensure accuracy of disaster procedures and practices.

The team’s use of video games as digital interactive environments began in 2018 with a proof-of-concept pilot study. In 2019, the team received a four-year, $559,617 grant from the National Science Foundation in support of the project.

Last fall, the team released their first game to the public, aptly called Cascadia 9.0 (available at Cascadia9game.org). The video game is designed to evoke the experience of a real-life earthquake.

Active Gaming vs. Passive Searching

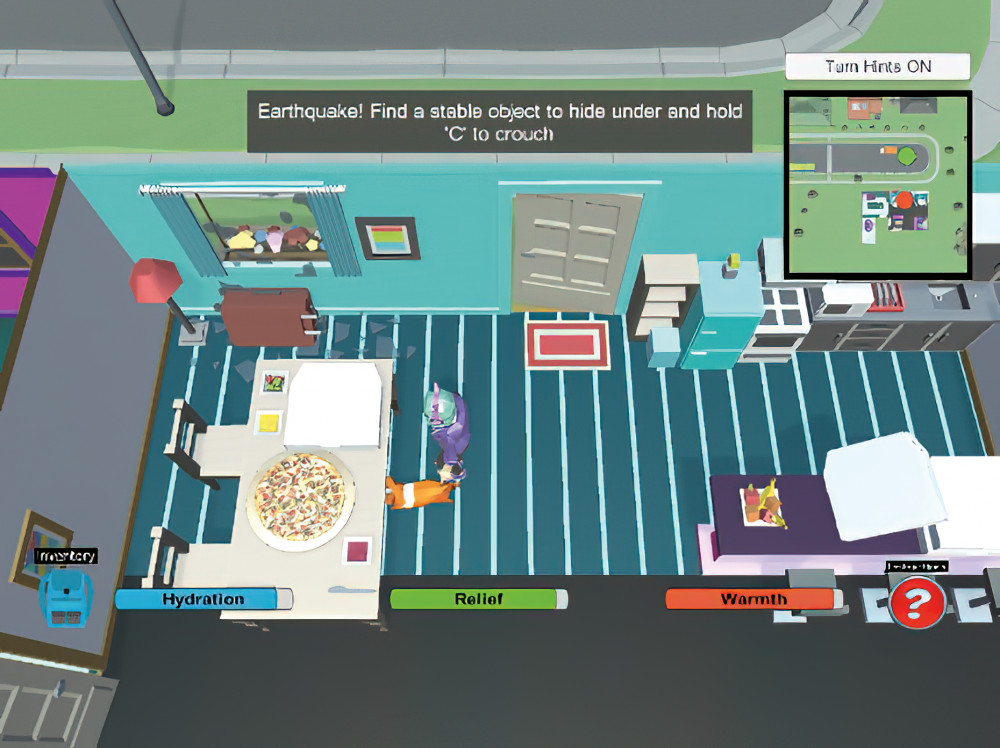

Zelda, one of the characters in Cascadia 9.0, is in her home when an earthquake hits and shelves and ceiling fans fall to the ground. She’s okay, but her corgi, Tsu (short for “tsunami”), escapes.

In a dizzying search for her dog, Zelda must tackle a variety of situations: she must prevent a gas leak, find shelter, purify drinking water, and more. By the time Zelda is reunited with Tsu, the player knows how to handle a variety of problems that arise before, during, and after a major quake.

According to Sebok, the overarching theme of finding a lost dog “drives the narrative forward.” The theme is designed to give the game emotional weight.

There’s strong evidence that tools like video games can be more effective than traditional media when it comes to immersing audiences. Instead of watching videos on how to prepare and respond to an earthquake, players can have that experience for themselves.

“Active learning—actually struggling to do the task in question— is more effective than passively absorbing information from a book or a lecture,” says Drake.

In Safran’s words, “Sometimes what is not real can really help you grasp what is real.”

The team thinks video games are an especially effective way of messaging to young adults because of their media preferences; however, the games could be helpful to others as well. “Video games are a popular medium for many demographics within our culture,” Sebok says. “They are potentially dynamic learning tools.”

The Team’s Research

Alongside the public release of Cascadia 9.0, the research team is conducting a series of experiments on what motivates preparedness behaviors, sharing their results with Portland’s emergency responders.

In their most recent experiment, which concluded in early spring 2022, the researchers created a treatment group that played the video game and a control group that searched the internet for information. Using pre-experiment and post-experiment survey data, the researchers analyzed what participants had learned and how it affected their motivation or action toward preparing for earthquakes. In addition, they ran focus groups to gain more insight into what participants were thinking.

“We were trying to get some basic understanding of what people can learn from games and what games can do to boost people’s intentions to prepare for earthquakes,” Safran says.

In analyzing the data, they found that participants within the video game group spent longer on their task, downloaded more information right afterward, and felt more confident about coping with some key earthquake-related challenges, such as finding and purifying water and practicing good sanitation.

“We discovered that the elements they seemed to remember best and reflect on were those that required ‘stickiness,’ where they had to go through a series of actions or problem-solving to be successful in the game,” Nilsen says.

The gamers were also more likely to inquire about training opportunities embedded in the game, such as those offered through Portland’s Neighborhood Emergency Teams. These teams train residents to provide emergency disaster assistance in their own neighborhoods.

We certainly want to steer people between the two extremes of ‘It’s nothing I need to worry about’ and ‘We’re all doomed.’ Preparing now can make the difference in surviving and thriving in the aftermath of the inevitable Cascadia Subduction Zone earthquake.”

Peter Drake, Associate Professor of Computer Science

Drake says working on the game has inspired him to be trained as a neighborhood responder and have his house seismically upgraded.

The team has worked with local emergency groups, such as Clackamas County Emergency Management and the Portland Bureau of Emergency Management, to craft the game to ensure the narratives are realistic. Safran adds, “On the flip side, we have been able to point out gaps in their web messaging content.”

The team has presented their results to about 40 regional emergency managers. They’ve also shared updates on what they’re finding to be effective ways to message about disasters.

When Cascadia 9.0 made its public debut, it was shared via social media by Washington and Oregon emergency management agencies, triggering a burst of play. More than 5,500 users have played the game so far.

-

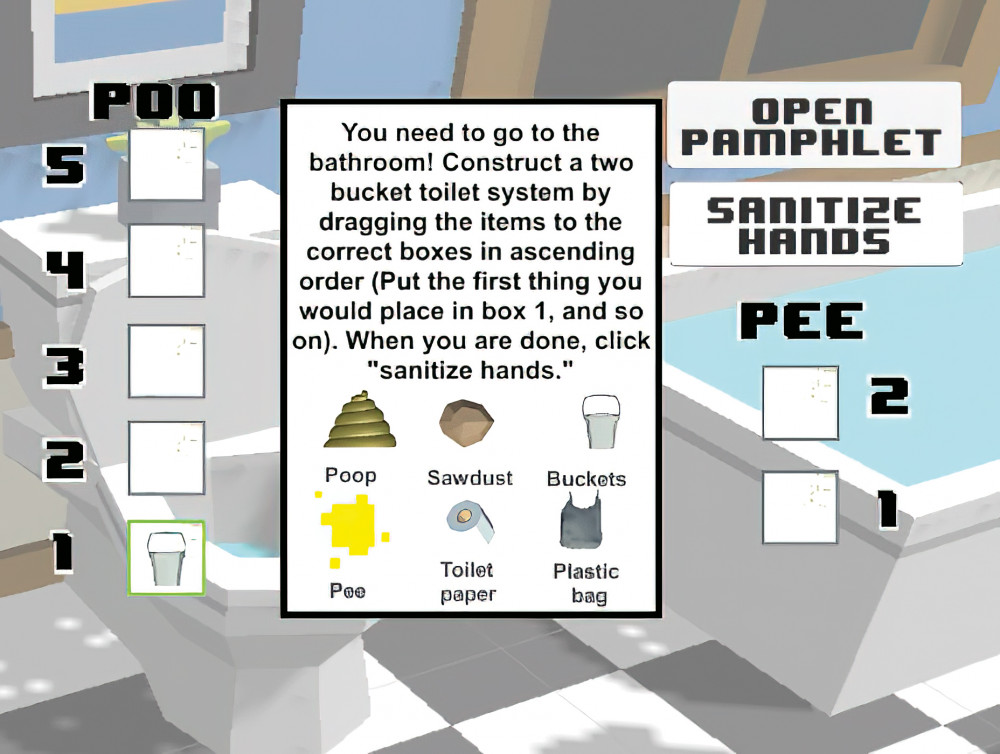

Screenshots from Cascadia 9.0. The game is available for play at cascadia9game.org.

Screenshots from Cascadia 9.0. The game is available for play at cascadia9game.org. -

Screenshots from Cascadia 9.0

Screenshots from Cascadia 9.0 -

Screenshots from Cascadia 9.0

Screenshots from Cascadia 9.0 -

Screenshots from Cascadia 9.0

Screenshots from Cascadia 9.0 -

Screenshots from Cascadia 9.0

Screenshots from Cascadia 9.0 -

Screenshots from Cascadia 9.0

Screenshots from Cascadia 9.0

What’s Next

Cascadia 9.0 is only the first of a series of games aimed to prepare users for the Cascadia quake. Safran thinks it’s a good start. “I’m pretty pleased with the first game,” she says. “It covers Screenshots from Cascadia 9.0 a lot of territory. We had to make it that way because it needed to be sufficiently information rich to compare with the web, which has all the information.”

Moving forward, the research team is planning additional experiments that will build off the data they have gained thus far. They will use future games (Cascadia 9.1, 9.2, etc.) to explore the importance of cooperation, environment, and social reinforcement on motivation to prepare. They also hope to make upcoming games available on smartphones, making them more accessible and user-friendly.

Drake hopes the games will encourage other Pacific Northwest residents to prepare for earthquakes, just like he did.

“We certainly want to steer people between the two extremes of ‘It’s nothing I need to worry about’ and ‘We’re all doomed,’” Drake says. “Preparing now can make the difference in surviving and thriving in the aftermath of the inevitable Cascadia Subduction Zone earthquake.”

This material is based upon work supported by the National Science Foundation under Award No. 1917149.

Student Researchers Join Forces With Faculty

More than 50 students have worked on the project over the past seven years

Lewis & Clark’s earthquake preparedness project has united students across departments, from computer science to psychology. More than 50 students have worked on the project over the past seven years, programming the game, developing survey materials, and helping with data analysis. Dozens more have contributed to areas such as play-testing and edutainment strategies.

Associate Professor Peter Drake, who is in charge of overseeing the game’s programming, says students have been “absolutely essential” to this project. “There are so many possible angles for involvement.”

The project also has tie-ins to several courses, such as Drake’s Software Development and Associate Professor Liz Safran’s (Un)Natural Disasters. Students often work on the project through the summer through the John S. Rogers Science Program.

Sylvia Kunz BA ’23, a psychology major, was one of those students who participated in the summer research program; she then went on to accept a year-round position as a research assistant with the team. She’s designed surveys and collected and analyzed data.

Through her work on the team, Kunz says she has learned about the importance of investigating preventative measures—something that has informed her career plans. After graduation, she intends to support people who’ve experienced traumatic events.

“Contributing to this project has expanded my ideal clinical scope to include survivors of natural disasters,” she says.

Kunz’s lab partner, Jensen Kraus BA ’21, a psychology and Hispanic studies major, also says that working on the project has influenced his career choices. He’s currently pursuing a master’s degree in social work from Portland State University, where he’s been able to apply his experience analyzing large data sets.

“I think it’s easy to get overwhelmed by hundreds of participants and thousands of data sets if you haven’t done this work before,” Kraus says. “I took statistics in undergrad and in grad school, but nothing has been as in-depth as my work on the earthquake preparedness study.”

Another important takeaway for Kraus: There are people behind the numbers. He ran participants through the earthquake study and was in charge of answering their questions.

Even though much of the data he analyzes now is from anonymous participants, he says he always tries to consider the experience of the survey takers. “This allows me to be very reflective in the way I look at the data,” Kraus said. “It helps me not be judgmental or jump to conclusions.”

In addition, student researchers say they are more prepared for a Cascadia earthquake after working on the game. Kunz says that, despite living in the Pacific Northwest her whole life, she was ill prepared for a quake. Her time on the project changed that.

“I have made it a priority to start taking steps to prepare and often share strategies with my loved ones in the Portland metro area.”

More L&C Magazine Stories

L&C Magazine is located in McAfee on the Undergraduate Campus.

MSC: 19

email magazine@lclark.edu

voice 503-768-7970

fax 503-768-7969

The L&C Magazine staff welcomes letters and emails from readers about topics covered in the magazine. Correspondence must include your name and location and may be edited.

L&C Magazine

Lewis & Clark

615 S. Palatine Hill Road

Portland OR 97219