main content Data Processors

In a cross-school collaboration, Professors Greta Binford and Liza Finkel prepare middle and high school teachers to weave real-world data science into their environmental curricula.

By Emily Halnon

Photo by Nina Johnson

Illustrations by Loris Lora

In an era where data drives innovation and insight, two Lewis & Clark professors—one from the College of Arts and Sciences and the other from the Graduate School of Education and Counseling—are joining forces to ensure the next generation is ready to harness its power.

Greta Binford, professor of biology, and Liza Finkel, associate professor of teacher education, recognized a gap in 6th- through 12th-grade education: While data science is transforming the workplace and informing the world’s most pressing issues, it’s still not part of the core curriculum in most middle and high schools. Too often, teachers lack the tools to incorporate data science into their classrooms, leaving students unprepared for today’s data-rich world.

“We have the opportunity to change this reality,” Binford says. “We are creating on-ramps for students and teachers to be comfortable with the practice of data science so they can apply this lens to real-world problems.”

Finkel, with her background in teacher training, saw an opportunity to integrate elements from Lewis & Clark’s Teacher Pathways program into the effort. Teacher Pathways is a partnership between the undergraduate college and the graduate school that supports undergrads who want to become teachers.

With their combined content and programmatic expertise, Binford and Finkel launched a yearlong professional development initiative on data science skills for local 6th- to 12th-grade STEM teachers as well as undergraduates who are interested in teaching careers. This collaboration was supported by a grant from the National Science Foundation. Participants used conservation topics as focal points for curriculum development, since the pair believes data science is a valuable tool for considering these issues.

The L&C students honed their data science knowledge through college classes and took the lead on developing and teaching the lessons. This model gave the undergraduate students a chance to make meaningful contributions in a professional setting and gain valuable classroom experience in the process. For Binford and Finkel, the goal is to distill lessons from the initiative and develop a scalable model that teachers can use to build data science curricula.

“We had undergrad students who shared data science knowledge and teachers who showed students how to plan and teach science,” says Finkel. “Everyone was contributing to the success of the program.”

Salmon Restoration in the Columbia River Watershed

Tumwata Middle School, Oregon City

Henkle Middle School, White Salmon, Washington

Seventh-grade science teacher Emily Bosanquet believes it’s vital for students to learn about the power of data. When she learned about the opportunity to partner with L&C on creating a data science lesson for her curriculum, she was immediately interested.

“Being able to analyze and interpret data is a pressing skill for middle school students,” says Bosanquet. “I felt like working with a college student would create a more engaging way for students to learn those skills—and it would allow them to see themselves doing data science in the future.”

“We wanted students to use data to consider the driving question about why salmon populations are changing and how dams are impacting them,” says Mobley.

Olivia Spagnuolo BA ’24 taught the students how to use data to analyze the role of dams, which are one of the greatest threats to the size and health of the salmon population because they change the natural flow of the river and present a challenge to migrating fish.

Spagnuolo started by giving the students an overview of coding and explaining how it can be a helpful tool for turning big datasets into digestible information to explore big ecological questions. She introduced the concept by having them pretend to be computers and give commands to each other to move around the room as if they were being coded. As expected, the students responded positively to their young teacher and her approach. That was a common theme across all of the classrooms that participated in this program.

Introducing data science into the curriculum was a chance to get them to think about where those numbers come from, what they mean, and what impacts they’re having on the community.”

Spagnuolo then presented the students with data for the salmon return rates over time at the Bonneville and The Dalles Dams and asked them to analyze patterns across the data. The students also visited the Bonneville Dam so they could tour the facility and see the fish ladder, which is a structure intended to create a safe passage for salmon. During the tour, Spagnuolo noticed that the students were using their new data science skills.

“They were questioning what they were hearing on the tour because some of the information didn’t match the data,” said Spagnuolo, who’s interested in going into teaching herself and valued the chance to learn from two seasoned professionals.

“It was exciting to see students make the connection and use their new data science skills to think critically about the information they were receiving.”

Both teachers plan to incorporate data science into their classrooms again this school year because they want students to be equipped to do exactly that.

“Students are living in a day and age where there’s so much data around them, from their phones to their computers,” says Mobley. “We want them to understand how to interpret data, make sense of the information they’re receiving, and be able to think critically about it. That’s a life skill that will help them regardless of what disciplines they go into after high school.”

Air Quality in Portland

Parkrose Middle School, Portland

Milwaukie High School, Milwaukie

Parkrose Middle School sits across the street from a controversial piece of land in Northeast Portland.

Last summer, a former Kmart building caught fire and unleashed ash and toxic debris into the surrounding area. And now, the site is slated for the development of a freight warehouse that could see traffic from as many as 1,600 trucks a day.

When she learned about the data science program through Lewis & Clark, it seemed like a great way to engage students on an environmental issue that directly affects their lives.

Leah Bandstra had the same idea for her students at Milwaukie High School, which isn’t parked next to a trucking facility, but has seen its fair share of poor air quality due to smoke and wildfires.

“Students are really familiar with the different things that can mess up the air quality and the need to check the Air Quality Index at certain times of year, especially during wildfire season,” says Bandstra. “Introducing data science into the curriculum was a chance to get them to think about where those numbers come from, what they mean, and what impacts they’re having on the community.”

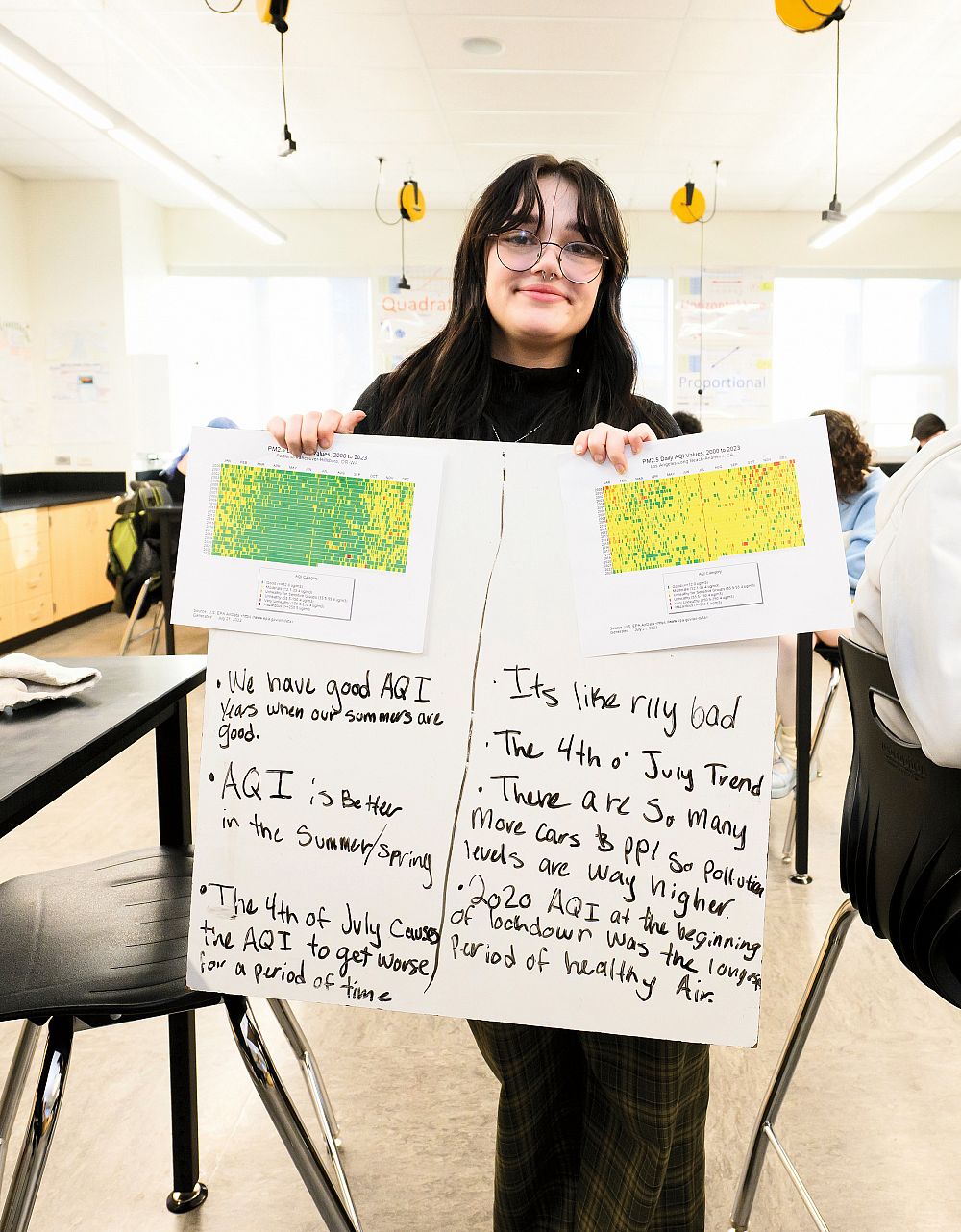

Kaitlyn Wright BA ’24 worked with the pair of teachers to integrate relevant air quality data into their curricula. She drew two decades of data from the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and created visualizations comparing air quality in Portland and Los Angeles so students could analyze the differences between the two cities and see how things like traffic, industry, and population can affect air quality.

“Using data visualizations to identify patterns is so impactful, especially with environmental issues,” says Wright, who majored in environmental studies and loves using data science to consider environmental questions.

“It was really exciting to see the students make connections between air quality and the different things that are influencing the Air Quality Index.”

She said the students noticed patterns like a dip in air quality every July 5, presumably from fireworks, and a noticeable improvement during the pandemic when fewer people were on the road. They also easily identified the connection between a huge degradation in air quality in Portland in September 2020 and the Labor Day fires that forced them indoors for days.

The students in Waksman’s class also studied what’s happening in other cities with trucking facilities and composed letters weighing in on air quality, using data to support their arguments.

“It was such a good opportunity to create a curriculum that students would actually like and engage with,” says Waksman. “They got to see how data is directly connected to something that affects their lives in many important ways.”

Sea Level Rise on the Oregon Coast

Adrienne C. Nelson High School, Happy Valley, Oregon

Nancy Mitchell, a science teacher at Adrienne C. Nelson High School in the North Clackamas School District, had used data in her 10th-grade chemistry class before.

She specifically wanted to integrate stronger data into a lesson on sea level rise, where students learn about thermal expansion of ocean water, a molecular process linked to rising temperatures from climate change. This phenomenon is affecting coastal cities across the globe, but Mitchell suspected students would be more engaged if they could see how it’s playing out in familiar places.

The partnership with L&C was the perfect chance to insert more compelling data into this lesson.

Mitchell worked with Isabel Kuhl BA ’25, who pulled decades of data from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) to create datasets and graphics that compared coastal regions in Oregon and Maine.

Using the visualizations Kuhl created, the students talked through the differences in sea level rise between the East and West Coasts and considered the factors that could have contributed to changes over time.

“Without having such engaging data tables and graphics to look at, it would have been really difficult for my students to try to see connections in the data and make some of those same conclusions about the rate of sea level rise,” Mitchell says. “The data and graphs that Bel compiled definitely led to a richer classroom discussion.”

Kuhl herself was actually not that interested in data science before she got involved as a student teacher. She was drawn to participating in the program because she was considering a career in education and wanted to get an inside look at being in a classroom.

But as an environmental studies major, she quickly appreciated the value of data science and found herself applying her new skills outside of the classroom.

“This program made me appreciate that we’re not always seeing the full truth in the information and news we consume,” says Kuhl. “It’s given me tools to consider where data is coming from and how I can use data to get a more accurate idea of what’s going on in the world.”

More L&C Magazine Stories

L&C Magazine is located in McAfee on the Undergraduate Campus.

MSC: 19

email magazine@lclark.edu

voice 503-768-7970

fax 503-768-7969

The L&C Magazine staff welcomes letters and emails from readers about topics covered in the magazine. Correspondence must include your name and location and may be edited.

L&C Magazine

Lewis & Clark

615 S. Palatine Hill Road

Portland OR 97219